Zambian “industrial break” means that everyone goes off before Christmas and comes back middle of January. Luckily there is KTM Zambia and they agreed to come out on the 28th to help me fit the electric starter clutch (for the 3rd time) and see if there is anything we could do about the bomber exhaust. Kotilda is leaking exhaust where the pipe is connected to the engine. Not only does it scare the animals and villagers, it is so loud it is hardly hear my own thoughts when riding.

A bit out of Lusaka we find the KTM sign on a massive compound. That’s how better off Zambians live, 10 acres of a garden all walled off with a nice house in the middle. That’s where he had his shop set up. 50 odd motorcross bikes, 4-5 new Dukes and Enduros on sale. We strip down Kotilda and find that the flange connecting the exhaust has completely broken off. Looks like the exhaust has just been dead weight on the bike and all the noise and fumes have come out directly from the engine. We don’t have a spare, but with the welding machine and some creativity we’ll have soon constructed a new connection. It won’t last forever and will rattle off, but it will give us some miles. Next we swap the gears on the starter clutch and find that the new clutch is already in pieces. That too will get put together with some wire, without any hope it would last long. Finally there is the question of lack of power at low RPM. The mechanic thinks it is a compression issue, “When did you last change your piston?“. That question came leftfield. “Umm, Never.” The mechanic shakes his head like I’ve already grown accustomed to. Luckily I also haven’t adjusted valve clearance forever. We found there was no clearance. Much easier to fix than the piston.

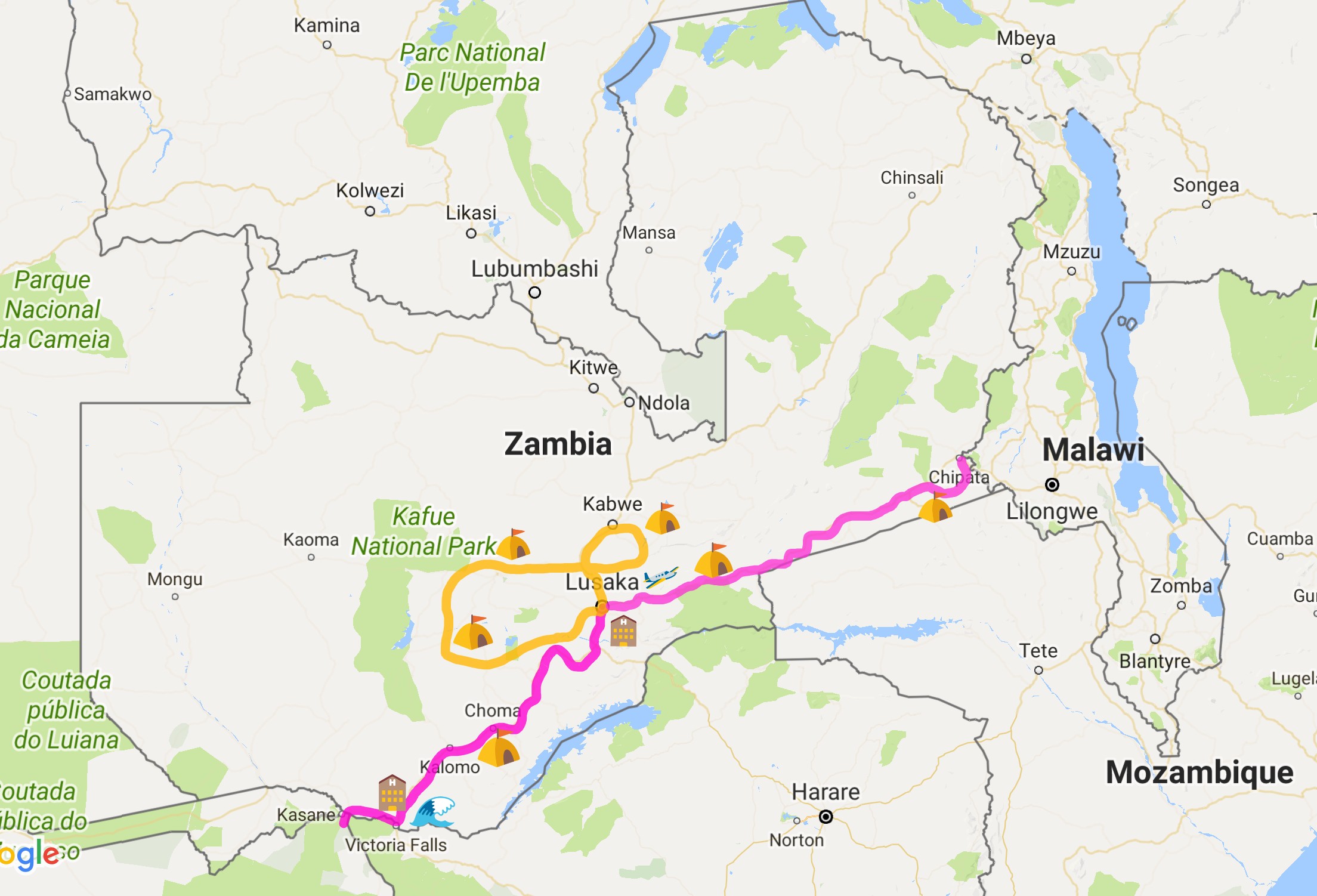

On the “great east road” to the Malawi border we get the feel for the vastness of this country. There is another 600km to go as the perfect EU funded tarmac winds through lush mountain ranges. It’s a pleasure to ride now that most of the exhaust ends up in the muffler and valve adjustment has made Kotilda go much smoother. The issue that the engine starts bogging at low RPM and wants to die on me if I ease the throttle hasn’t gone away. On the tarmac at high speeds it doesn’t matter.

Here we meet first travellers on this trip, Ali and Grace are Kenyan bikers on a massive 1290cc big mama sister of Kotilda and a much nimbler 500 EXC.

Long distances on tarmac leave plenty of time for thinking. For hours you have noone to talk to, no slack or messages to check. Literally nothing to do. I get to think about my brother a lot. It is two months since I got the phone call that he is gone. I got to spent more time with him in the last couple of years, but by far not enough. When we realised a year ago that his mind is developing an alternate reality I was thinking of inviting him along to this stage of the trip, thinking disconnecting in Africa would do him good. I never got the chance.

There are at least 10 times more bicycles on the highway than cars. In Malawi we’ll find that in addition to bikes there are 100x more people walking on the curb. So there is 12 meters wide road for cars that barely gets used and 1 meter of tarmac separated by a painted line on each side that gets heavily utilised by bikes and pedestrians. I was thinking of the poor guys in Scandinavia who design and build bike roads next to major roads, which only get used 2 months in a year – they would be so happy to put these roads into Zambia and Malawi. People are driving responsibly here, but would probably save a few hundred lives every year.

The other good news is that the mango season has started. All you need to do is stop near a mango tree, lie down, open your mouth and you can be sure one falls in soon enough.

We decided to take the new year in Lilongwe and now we’re getting there too early. Time to put the 3rd rule of motorcycle travel to use – when there is a choice between a short route and a long one, then always take the long one. The map shows we can do a 200km detour on smaller roads in the south near the Mozambique border before we get to Malawi. We just don’t know what kind of road that is – is it going to be 2 extra hours or 2 extra days. At first it is the African gravel, then after 50km we turn onto a single track and we get to the “road”. It is hard to know if it used to be a road long time ago or is it just not ready yet.

Kotila is splurting, bogging, slurring, choking at low RPM and guzzling petrol. We hesitate a bit, whether we’ll have time and fuel, but we decide to push on. Soon we hit our first obstacle – a creek flows through the road with high banks. We couldn’t see any motorcycle tracks go through, there are certainly no car tracks on this road either. We’ve taken plenty of tracks that are too narrow for a 4×4, but we’ve never taken a road that the locals aren’t taking wth their 125cc little bikes. A cyclist comes our way. We ask if this road can be passed on motorcycle. He says no. “Only bicycles,” he explains in sign language and walks his bike through the ditch. Sun is going down and we now have an option to return or set up camp here and ride back tomorrow. But if we’re already staying here, why not try to cross that ditch and ride to the next obstacle?

We’re waiting for this impassable obstacle to show up, but the path gets even a bit better. A few simpler ditches and it is hard work to keep Kotilda’s engine revving and not dying. She does better when she goes fast, so I let her. On one occasion speeding up a sandy hill with an open throttle I see Juka and Suuzi emergency braking for a small ditch. So do I, but expectedly Kotilda’s engine dies and I’m flying into this ditch without any traction or control in the soft sand. She doesn’t mind much. I just have to stop and pick up all my personal belongings that burst out of the luggage as they flew open on impact.

Only after 10km of nonexistent road, there is suddenly brand new tarmac. But only briefly, 10km later we’re back to the normal earth road. The roadside is a neverending village, we turn onto a track through the maize and tobacco fields and a few kilometers inland find a perfect spot for camp. As the sun sets the drums are already beating in the village, but we have something much more important to do. It is time to lay the table for the Christmas dinner. It is already the 30th of December and I’ve been carrying Estonian sauerkraut and blood sausages in my luggage exposed to the tropical heat.

It is past midnight and the drums are still going in the village with singing and yodeling. I know plenty of people at home, who enjoy a folk song and dance now and then, but I can’t imagine anyone going on for 6 hours. Earlier on that dirt road we saw a group of villagers gathered around 10 people with animal skins around their waist doing their dance with spears to the beat of the drums. This sight was exactly out of the Nat Geo channel, but I don’t think there was a Canon camera in a 200 mile radius. I honestly thought this kinda dance is performed only for cameras and toursists these days. It was somewhat relieving to see that this is what folks still do when no-one is looking.

Sunday morning everyone goes to church. Well, mostly women go to church.

Men go cycling.