I open the throttle, but the thump of the 640cc cylinder doesn’t save me. The bike skids into the mud. I pick up the bike, kickstart and try to get going, but the rear wheel spins and Kotilda doesn’t move more than an inch. I try pulling back and it moves an inch, no more. The reason I crashed wasn’t just my incompetence – my front wheel is stuck.

It didn’t rain last night when we camped in a deserted village of 4 huts and a tombstoned grave from 2012. Probably the kids had moved away and when the grandma passed, they buried her in the front yard, boarded up the windows and left the place to rest. We thought 4 years was enough rest and they wouldn’t mind if we very politely camp there. As we packed up in the morning it started to rain and kept us hiding under the roof extension of one of those huts. I wished they were more generous with their roof extensions, standing up for 4 hours next to the wall under the cover of 40 centimeters got quite tiresome by the end.

The next realisation was that the moderately technical road had become seriously demanding when wet. There were little ponds across the road offering 20 meters riding in the water. You ride into one and don’t even now what to expect. When the nose suddenly dives deep you just add throttle and hope you come out the other end, doesn’t matter if you’re in up to the chest or not.

These ponds were just an inconvenience, the real issue were the stretches of clay that could be up to a kilometer long. It’s slightly grey compared to the usual red dirt, which just get’s slippery. The clay sticks to everything. The locals build their huts from this stuff. It’s straightforward – collect the clay, put it into a rectangular shaped wooden frame, let it dry in the sun, burn a bit on the fire and voila – you have a brick. Attempting to ride through this wet clay turns the knobbly rubber tyres into slick clay wheels about 2 inches larger in diameter. Now my front clay wheel had jammed into the front mudguard. The wheel is stuck and that’s why the bike doesn’t move. My fix involves tightening the mudguard to forks with some extra cable ties and forcing the front wheel to move around. It brings me out of that clay river but only as far as the next one and I’m now completely stuck in the middle of the road with clay as far as I can see the road. There is no way out and it is starting to get dark again. We have only moved about 35 tough kilometers today.

Juka doesn’t have that problem with Suusi, his splashguard is up high like the motocross bikes. The solution is to copy the other bike. Knee-deep in the mud with my boots getting heavy with another inch of clay now attached to them we decide to take off the mudguard, which is reasonably straightforward once we removed one of the brake calipers and strapped it to the top of the forks. Then we strapped the mudguard to the forks too, effectively increasing the space between the wheel and the plastic by 20cm.

It worked. Plenty of mud and clay splashing into my face, but we’re moving again and it’s not completely dark yet.

Last night started like a beautiful camping evening. Behind one of the huts was a cleared patch large enough to fit our tent and bonfire for teamaking. We had a tent with a netted window and door where you can breathe and keeps mosquitos out. But we couldn’t sleep and it took us a few hours to figure out we were infested with tiny sand-flies. These are 1 mm across, nearly invisible flies that come through any mosquito net and bite the hell out of you. Especially when there’s hundreds of them and just the two of us to kill them. Impossible, we thought 2am after haven’t been able to get a minute of sleep. Then we remembered there was a little bottle of Boots tropical strength mosquito killer that our most prepared companion Kriss had left with us just in case. We were quite certain it doesn’t work on the flies, but as the last resort and against all instructions replaced the air in the tent with the deadly chemical. Boots was a night saver and gave us a good few hours of sleep before the sun came up.

Mbengwe tea party

We didn’t want the same experience tonight and didn’t have any light left to look for a good spot, instead we rode into the first village and went to speak with the chief. Chief Pedro said it is okay. We can set up camp in his front yard. Well, it is quite hard to know what’s his front yard and what’s not. It feels like the whole village is everyone’s front yard at the same time. By the time we’ve parked Kotilda and Suusi under the communal mango tree, we have the full house waiting for today’s entertainment. There are two rows of people, from kids to young men standing two meters away from us and quietly watching. About 25 people have gathered for the show. We don’t mind, but we don’t know what’s the entertainment meant to be, other than us having to perform it. I escape the awkwardness and go to fetch the water from the village well, leaving Juka to figure it out.

When I’m back with water he is visibly stressed out by the waiting audience. The audience has all the time in the world. Our first miserable attempt is opening our foldable tent. One of the older dudes murmurs in French, that it would be handy to have such a petit maison, when he goes hunting. But otherwise there is almost no reaction from the audience. Next we bring out our teapot. There is an always-on little bonfire going on in the outdoor kitchen. We make a strong Yunnan blend tea and offer it around for the older dudes in the audience. They consistently called it coffee regardless how many times we explained it is tea. I guess that is all some weird dark hot liquid that the white man drinks to his pleasure. The tea round finally breaks ice and we chat long hours in French into the evening with Pedro, Janick and Antoine about their job – hunting food for their family, forest life, animals, trees, fruits. I’m quite embarrassed that I’m already a middle aged dude and I still haven’t learned to speak French. Fortunately Janick had an amazing skill – he danced the stories. Whenever someone told their hunting story and I didn’t understand then Janick took over, read the same story in what sounded like French poetic rhyme, moved his arms, legs and torso around to match the rhyme and was semi-related to the story. Most of what I learned that night was dance-translated by Janick.

Since the legendarily impassable Nigeria-Cameroon border crossing got paved a few years ago, then this 300km dirt road stretch is one of very few remaining unpaved sections before you can get from Morocco to Capetown on tarred roads. Many people have cycled through all of Africa already, I’m convinced that the first time someone roller-blades the entire route is only a dozen years away.

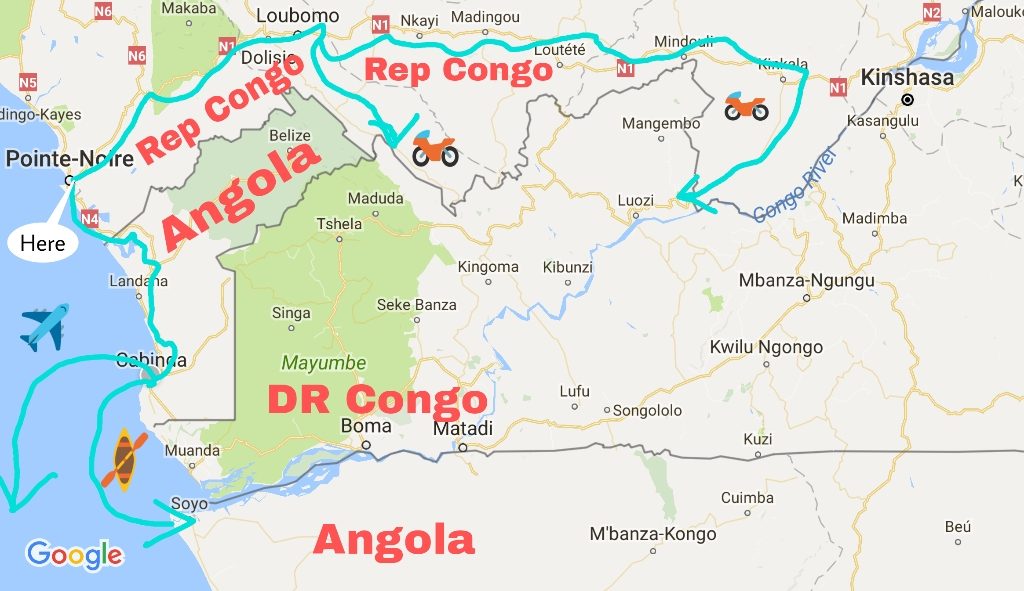

We’ve adapted our DRC strategy and taking the bet on the Angolan consulate in Point Noire on the coast, the capital economique as our village friends described it. The Congo river is not navigable from the coast to Kinshasa/Brazza because of rapids. It’s believed that the lack of navigable rivers is the reason why the history of sub-Saharan Africa isn’t as prosperous as the other continents. As you can’t get merchandise in and out of the colony on the river, the French decided to build a railway to connect the port of Point Noire with Brazzaville above the rapids. 17,000 dead railway-building congolese later we have a functional railway deep in Africa. I think there is plenty of cargo moving on the track today, although we didn’t spot any trains. There should also be a passanger train a couple of times a week. These days it is about the oil. Platforms operated by Total and ENI are just a few miles off the coast. The pipelines bring the crude to the shore, load it onto tankers and off it goes to the refineries in Europe. Beautifully isolated from the rest of the country. Chatted with a Frenchman Jacques, who works as a skipper on the boats maintaining the platform just off the coast of Point Noire. Like Deleur he is here for the much higher pay than European jobs can afford. When in Libreville you would bump into a white French person every couple of hundred meters then Point Noire is rather noire. In Congo we met probably 30,000 locals before running into the first expat in Point Noire. Looks like here it is just the rig workers and no-one else.

The long day of 200km of dirt-clay-puddle-cobble road and another 200km of zigzagging tarmac through the mountains was topped off by entering the city through its only road through miles and miles of bustling suburbs where a line of trucks, beaten up toyotas and the occasional private car were inching towards the centre. Kotilda overheated twice until I diagnosed the lack of coolant, although I had filled up in Libreville. Adding the coolant solved the issue. We took the cheapest hotel of €70, which ended up being okay bungalows near the beach and crashed after 18 hours of hard work on a village omelet.

Angolan embassy had put out a sign that they’re on holidays until 4th of January. Good for them. We took to the drawing board. There are no positive news from Brazzaville, more travellers have reported to have been denied DRC visa there as they’re not local. We have two types of options left: 1) try out DRC border posts with the hope to somehow negotiate entry; and 2) ride to the Angolan enclave of Cabinda and find a way how to get around 40km stretch of DRC and the river that separates the enclave from the mainland and while doing this never get stamped out of Angola as we then couldn’t get back in. The challenge with the first is that the two DRC border posts this side of Brazzaville are all ca 150km through the bush from the main road. We’d potentially spend two days to get to a border post and then likely another 2 days to get back from there. The challenge with the Cabinda option is that once we’re there and if we fail to find a way to get our bikes across to mainland, we’d be stranded in the enclave without a visa to any of the neighbouring countries and the 5 day Angolan transit visa running out fast.

Researching on the overlander forums I stumbled on those fascinating reports of other folks in similar situation as us – a cyclist crossing Africa and taking a 14hr pirogue sailing from Cabinda to mainland and a French dude and his girlfriend negotiating a military plane to take their bikes to Luanda. We’ll sleep on it and be smarter in the morning.